The Medieval World 500–1450 CE

Metropolitan Museum of Art Spotlight Object

Lidded Box

Lidded box of Muhammad al-Hamawi, timekeeper at the Umayyad Mosque

Damascus, Syria

15th century

Brass engraved/inlaid with silver

10.2 × 17 × 8.3 cm

91.1.538

Credit: MET Museum | Public domain

This lidded brass box, engraved and inlaid with silver, exemplifies Mamluk metalwork, which otherwise began to deteriorate by the late fourteenth century. This particular box belonged to Muhammad al-Hamawi, the timekeeper of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, Syria, and probably served as a food container. Al-Hamawi’s duty as timekeeper was to supervise the adhan (call to prayer) as well as announce the beginning and end of Ramadan. The engravings and silver inlays proffer calligraphic inscriptions in Arabic bearing good wishes, prayers to Allah, and information about the commissioner and owner of the box.

Artemis Tzioli

Art History Program, VCUarts Qatar

The Big Picture

The Medieval era saw the rapid rise of intercultural exchanges from territorial expansion as well as the sophisticated development of land and sea trade networks. The most famous of these was the Silk Road, which connected the easternmost parts of China through Central Asia to reach the Roman Empire. Coins from the reign of Roman Emperor Theodosius II, found in China during the fifth century CE, illustrate this exchange. Famous travelers, such as the Venetian merchant Marco Polo or the Moroccan scholar Ibn Battuta, documented their journeys, leaving fairly accurate portraits of thirteenth century civilizations for scholars to consult.

One of the greatest powers to come from the Central Asian steppes were the Mongols, a nomadic people known for their brutal military might, agile horses, and skilled archers. Under Genghis Khan (1162–1227), the Mongols conquered most of Eurasia, reaching as far west as the Levant. The Mongols were also known for their love of art, and commissioned many works from Persian and Chinese artists under their rule, contributing to intercultural stylistic developments. Such blending was not unique to the Mongols. Greek influence can be found in many Buddhist sculptures from northwestern parts of the Indian Subcontinent as a result of Alexander the Great’s conquests; in a similar vein, Chinese silk and Persian rugs became luxury commodities in Roman territories.

Well before then, in the third century, a coalition of Germanic tribes known as the Franks had begun their expansion, ultimately gaining control of a large portion of Western Europe. One of their kings, Charlemagne (r. 768–800), was responsible for uniting most of Europe during the early Middle Ages. In 800 CE, he was crowned Emperor of the Romans by Pope Leo III, becoming the first Western emperor. Known as the Carolingian Renaissance, this marked the first medieval European cultural revival, which drew great influence from the Christian Roman Empire. While the Franks were renowned for their metal works and skilled craftsmanship, Frankish art became more representational, assimilating Christian Roman artistic styles.

Another important source of intercultural exchange was the Christendom of Europe, which began in the fourth century, when Emperor Constantine of the Roman Empire embraced and legitimized Christianity as a religion. The Byzantine Empire (also known as the Eastern Roman Empire), lasted through most of the medieval era before it fell to Ottoman conquest in 1453 CE. However, Christianity endured as the dominant religion of Europe and a major influence on art and architecture. The greatest challenge to the institutionalization of Christianity arose with the advent of Islam in the seventh century, which quickly became the fastest growing religion in the world. By the eighth century, Muslims had conquered most of North Africa and reached Iberia. During the Islamic Golden Age, many ancient Greek, Persian, and Indic texts were translated and extended. Through contact with Islamic scholars across the Middle East and in the southern parts of Europe, particularly Sicily and Spain, knowledge transfer led to translations of seminal classical texts into Latin, eventually serving as the foundation for the European Renaissance.

Artemis Tzioli

Art History Program, VCUarts Qatar

In Focus

The Byzantine Empire

Department of Decorative Arts, Richelieu Wing, Louvre

A series of political events between the fourth and sixth centuries led to the division of the Roman Empire into western and eastern sectors.

More

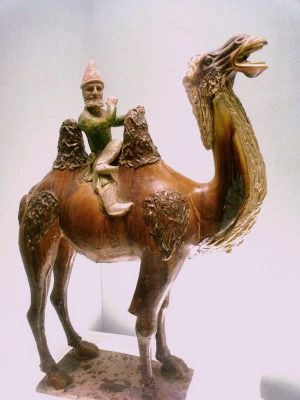

The Silk Road

Shanghai Museum, Shanghai, China

The Silk Road was a vast and expansive network of trade routes established during the Han Dynasty in China (206 BCE–220 CE), stretching across Eurasia from the coast of Japan into the Mediterranean.

More

Mongols on the Global Stage

National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan

The Mongol Empire has one of the most notorious reputations in history, with their infamous leader Genghis Khan unifying the segregated tribes of the Central Asian steppes in the early thirteenth century.

More