Diplomacy and Trade

Museum of Islamic Art Spotlight Object

Jahangir Album

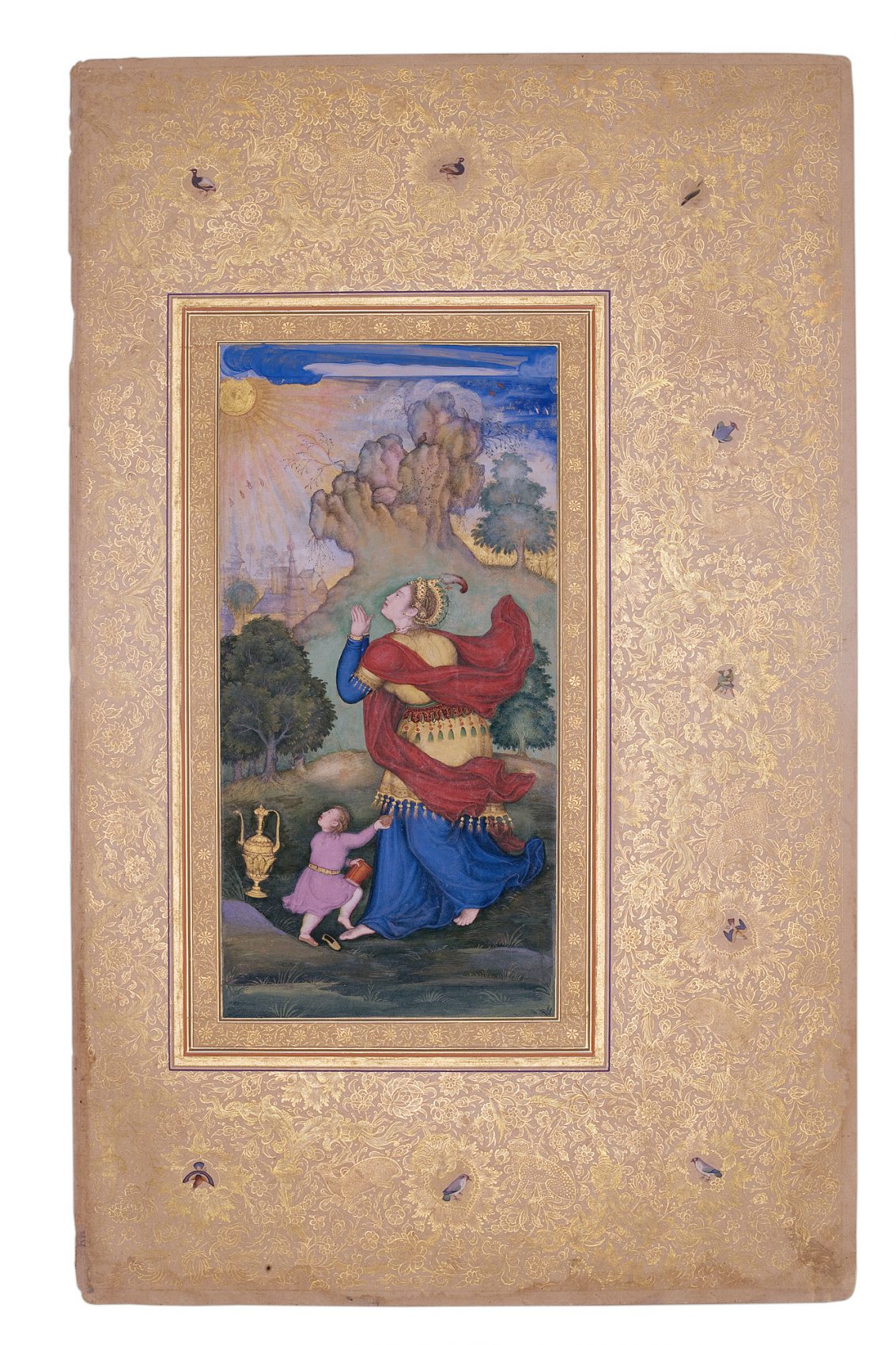

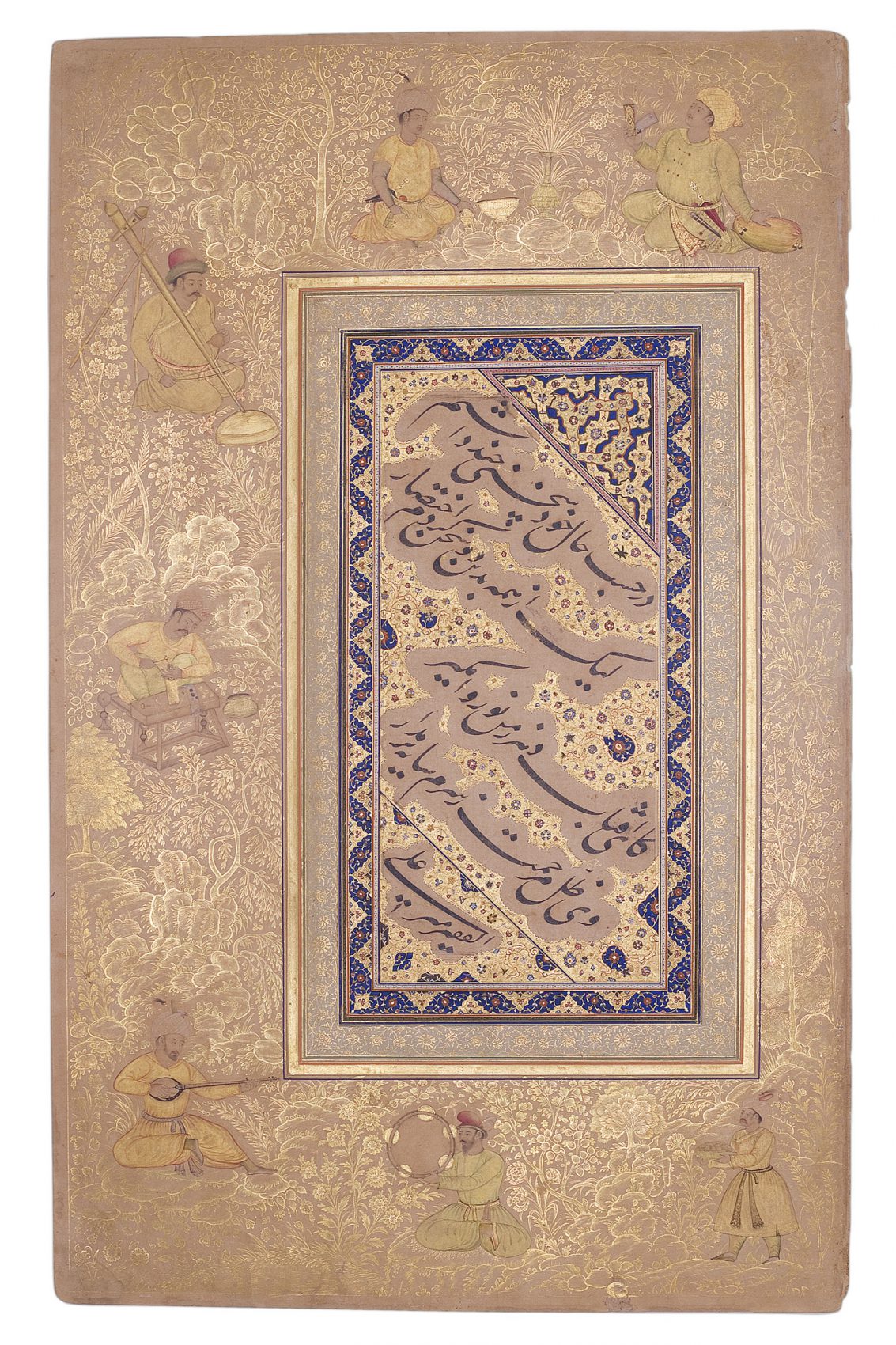

Page from the Muraqqa-e Gulshan or Jahangir Album

Recto: classical figure with a child

Verso: calligraphy by Mir Ali

Mughal, India

16th century

Ink, opaque watercolour, and gold on paper

42.5 × 26.5 cm

MS.157.2000

Credit: Museum of Islamic Art

Mounia Chekhab-Abudaya

Curator for North Africa and Iberia, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar

The Big Picture

Islam spread by both the word and the sword, but in early stages, it was considered an incoming force of tolerance, acceptance, and diversity in religious and social matters. By establishing Damascus as its first capital outside of Mecca and Medina, in a region previously under Byzantine rule, it thus recognized a diverse religious and ethnic population. Artistic styles began to merge, and diplomatic routes connected with far-flung regions. The pre-Islamic Bedouin Arabs engaged in commerce with the Persian Sassanid and Byzantine regions, setting up a foundation for a fruitful rise in diplomacy and trade as Islam expanded across political, social, economic, and geographic borders. The Islamic Golden Age, traditionally dated from the eighth to the thirteenth century, saw an increase in cultural, economic, and scientific sectors. In order to stimulate commercial activity, maritime trade routes, which pre-dated the Islamic record, were bolstered. The Silk Road offered another significant advance in Asian trade, allowing merchants from the Middle East, Europe, Central Asia, and East Asia to congregate. The Crusades were also a tremendous influence in this time period, dating from 1095–1291. Like the Pilgrim’s Canteen, countless Islamic artisanal works were brought back to Europe by the Crusaders, either as evidence of the journey, for the sake of exotic commodity, or to verify the triumphs of the Crusaders in re-Christianizing the Holy Land of the three Abrahamic faiths. Venetian traders also frequented Islamic cities in hopes of bringing back luxury goods, spices, and local materials found in the Eastern regions.

Artemis Tzioli

Art History Program, VCUarts Qatar

In Focus

Pilgrim’s Canteen

Freer and Sackler Galleries of the Smithsonian, Washington, DC

One of the masterpieces of Islamic metalwork is this lavishly decorated brass canteen from Syria.

More

Holbein Carpets

The National Gallery, London

This striking painting, while perhaps ordinary at first glance, compels attention for the many curious objects depicted within.

More