Early Visual Culture in Islamic Societies

Museum of Islamic Art Spotlight Object

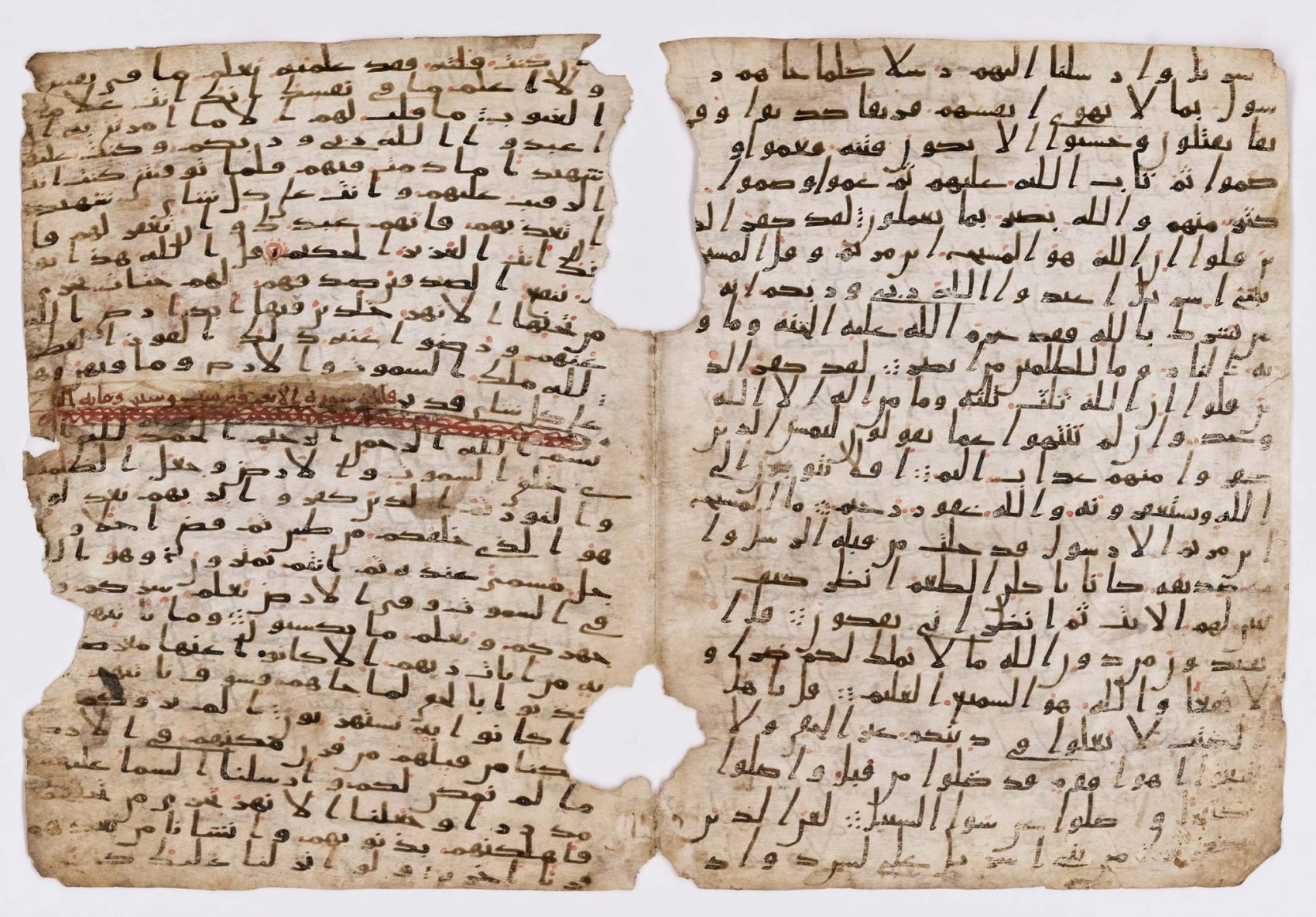

Bifolio of the Qur'an in Hijazi Script

Bifolio of the Qur’an in Hijazi script

Hijaz or Near East

Late 7th–early 8th century

Ink on parchment

33.5 × 49.5 cm (opened)

MS.67.2007.2

Credit: Museum of Islamic Art

The first Qur’ans were copied onto parchment in a vertical format using the so-called hijazi script, a reference to the Hijaz region where Mecca and Medina are located. Until recently, researchers were of the opinion that these folios, produced at the end of the seventh century and early eighth century CE, were made in this region. However, it is equally likely that the folios were copied elsewhere in the Middle East, given that conquests had already extended over a large part of the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East at that time. This type of format was supplanted by the “Italian format,” comprised of just a few lines per page in the far larger kufic script. These were made primarily for practical reading; presumably, their main purpose was to record the text in a format that made it easier to memorize.

Mounia Chekhab-Abudaya

Curator for North Africa and Iberia, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar

The Big Picture

In the year 610 CE, Prophet Muhammad received his first revelation from the archangel Gabriel. These revelations were written down in Arabic and compiled together to form the Qur’an. Muslims believe Muhammad was the last of the Judeo-Christian prophets and consider their Jewish and Christian brethren protected “People of the Book.” Islam is seen as a corrective to practices under the two earlier Abrahamic faiths, especially in its simplicity of direct worship to Allah. The Qur’an explains this relationship and provides guidance on leading a virtuous and just life.

Despite Islam’s initial unpopularity amongst the Meccan community and the subsequent expulsion of Prophet Muhammad and his followers to Medina, Meccans and the greater Arabian Peninsula eventually embraced the new faith. Under the Prophet’s command, the Kaaba in Mecca was cleansed of its pagan associations and rededicated as the focal point of prayer for all Muslims. The Prophet’s successors, known as caliphs, continued to spread Islam’s message, and in a short period, conquered a vast swath of land between the eastern borders of Iran and western points of Africa and Europe. Following the death of Ali ibn Abu Talib, the fourth Rightly Guided Caliph, a powerful governor of Syria named Muawiya seized power, established the Umayyad caliphate, and transferred the political capital of the first Islamic empire from Mecca to Damascus. As Muslim armies and peoples moved through new geographic spaces, they encountered diverse cultures with fully developed visual aesthetics. Early Islamic art and architecture borrowed heavily from these pre-Islamic visual traditions, as well as neighboring polities such as the Byzantine Empire. In short order, however, Islamic art blossomed into its own distinctive category based on the needs and preferences of thriving Muslim communities. At the core of this new visual expression was the ornamental development of Arabic script and the construction of large congregational mosques oriented toward the Kaaba. Within two centuries, scribal practices for Qur’ans and architectural features of mosques had been codified while remaining open to aniconic decorative influences.

As a caveat, it must be noted that “Islamic art” is not a religious classification alone. While sacred objects and spaces are certainly part of this expansive category, it nonetheless encompasses all arts from Islamic societies, including secular texts and structures as well as figural imagery.

Radha J. Dalal

Art History Program, VCUarts Qatar

In Focus

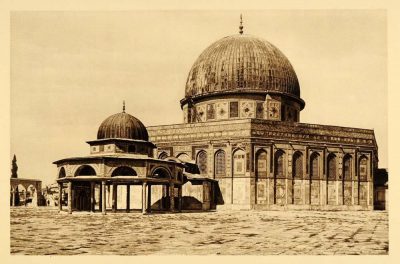

The Dome of the Rock

Jerusalem

Jerusalem’s connection with Islam begins with its early designation as the first qibla, the focus of prayer for all Muslims.

More

The Great Mosque of Damascus

Damascus, Syria

Similar to the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, the Great Mosque of Damascus rests on a site home to pre-Islamic structures.

More