Power and Patronage

Museum of Islamic Art Spotlight Object

Pen Box

Umayyad of Al-Andalus, Spain

11th century

Carved and painted Ivory with brass hinges

4.8 × 36.8 × 7.6 cm

IV.4.1998

Credit: Museum of Islamic Art

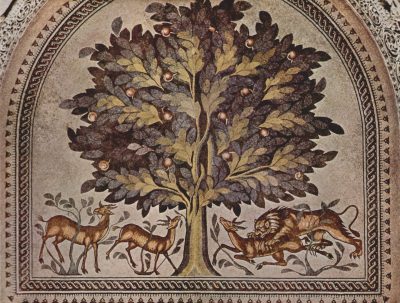

This pen box is representative of the production of carved ivory objects that were commissioned by high members of the court during the Umayyad period in al-Andalus (756–1031). An interesting example of ivory painted in black, it gives the appearance of ebony, equally valued in Islamic art. It features scenes of mounted huntsmen killing their prey with lances or themselves attacked by lions, alongside hunting falcons, hares, and mythical griffins. An inscription in kufic script wishes blessings to the owner, whose name is however unmentioned.

Mounia Chekhab-Abudaya

Curator for North Africa and Iberia, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar

The Big Picture

As the dominions of each successive Islamic dynasty expanded, modes of courtly conduct and communication developed into rigid rituals to elevate the image of the sovereign. Often these rituals were closely associated with the space within which they were expressed and with objects that conveyed the ideological bent of the current ruler. Palatial complexes of early Islamic centuries borrowed heavily from pre-Islamic traditions both in matters of construction as well as in the courtly ceremonial. Underscoring the ruler’s power and authority, palaces often incorporated lavishly decorated areas for entertainment, leisure, and the reception of grand audiences. Such assimilation and adaptation of foreign visual and ritual vocabularies helped situate the ruler within the larger context of global imperial identities. This responsiveness to external influences also positioned Islamic courts fairly well at the intersections of international networks of trade and diplomacy.

International trade led to an internationalization of fashion in textiles, ceramics, metalworks, and other portable luxury objects. Imperial wealth and power led to the establishment of royal ateliers that produced fineries for courtly consumption and diplomatic gifts—but under the strict regulation of a supervisory body, which thus indirectly governed elite taste. Royal processionals showcased these textiles with displays of regal pageantry intended to engage and impress the public. Gifts of robes of honor (tiraz) to ambassadors and ritual uses of elaborately embroidered cloaks during ceremonies introduced a political language understood across and beyond the early Mediterranean world.

Radha J. Dalal

Art History Program, VCUarts Qatar

In Focus

Khirbat al-Mafjar

Jericho, Palestine

Umayyad desert palaces adapted structural and decorative features from their Byzantine and Sassanian predecessors.

More

Roger II’s Mantle

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Silk was a prized commodity in the medieval Mediterranean world. Under Muslim rule, Spain and Sicily, unlike their northern European neighbors, did not have to import silks.

More