Worship, Study, and Commemoration

Museum of Islamic Art Spotlight Object

Mosque Lamp

Mamluk, Egypt (Cairo)

Mid-14th century

Enamelled and gilded glass

GL.1.1999

Credit: Museum of Islamic Art

Developed in Syria and Egypt between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries, the technique of enameling stands out as a truly innovative approach to decorating glass. Prominent examples bearing this technique include glass beakers, perfume sprinklers, and mosques lamps, often further embellished with gilt. Glass lamps such as this example were generally commissioned by rulers or wealthy patrons and hung to provide light inside mosques and madrasas. This particular lamp can be linked to the rule of the Mamluk Sultan al-Nasir Hasan (r.1347–51 and 1354–61), based on stylistic comparisons with similar lamps found in this ruler’s madrasa. Thuluth script encircling the neck reads in translation: “What was made for his Excellency, the Elevated, the Servant of the Lord, the Great Emir, the Possessor,” while written around the body and its underside six times is “The Learned.”

Julia Tugwell

Assistant Curator, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar

The Big Picture

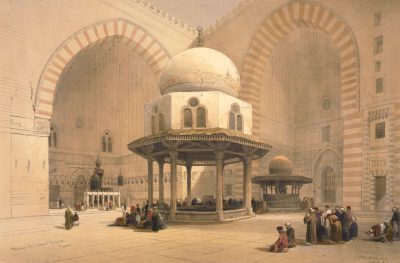

From the very beginning, Islamic rulers understood the value of patronizing building arts to directly mark the presence of Islam and indirectly amplify their own legitimacy. The Umayyad Dome of the Rock is a splendid case in point. With the succeeding Abbasid rule, architectural styles developed in the central Islamic lands of Iraq and Syria spread throughout the dynasty’s vast and unified domains. Over time, these foundational styles synthesized cultural affinities from far-flung lands and acquired distinctive regional elements.

Great Mosque of Kairouan, Tunisia. Credit: Marek Szarejko | CC BY-SA 2.0

Mosque architecture was at the heart of all construction activity. The simplicity of design in early mosques related to rituals of prayer, as any quiet and hygienic space oriented toward Mecca is suitable for prostration. In Prophet Muhammad’s time, his humble house served as the first mosque. The faithful gathered under a portico on one end of the courtyard, facing the Kaaba, and from its thatched roof Muslims were called to prayer. No matter how mosque architecture later evolved, these fundamental needs remained the same. Mihrabs began to grace qibla walls to better indicate direction for prayer; minarets towered to soaring heights, eventually becoming symbolic rather than functional; and hypostyle (many columned) plans were joined by those with large iwans (vaulted recesses) and domes raised on drums.

Mosques served the community in other capacities as well. For instance, scholars would often gather with groups of students in quiet, shaded corners to discuss and debate interpretations of the Qur’an and subjects beyond theology, such as philosophy, medicine, science, and literature. Such informal modes of education later developed into full-fledged university-like establishments called madrasas, where aside from religious instruction, they emphasized a holistic understanding of the world and its mysteries. With the emergence of this new institution came the need for architectural spaces specifically suited to its function. Madrasas were often annexed to grand mosques or tombs, depending on regional norms. Largely endowed by wealthy patrons, the commissioning of madrasas was seldom an act of unpretentious piety but rather a means to safeguard fortune and immortalize the benefactor’s name.

Grand tombs served a similar function. Following Prophet Muhammad’s example, early Islamic funerary practices generally favored austerity over ostentation. Unmarked graves were thus preferred instead of elaborate tombs. In time, however, pre-Islamic traditions of constructing royal mausolea deeply influenced Islamic rulers who sought to commemorate dynastic history. Upon a ruler’s accession to the throne, tombs often took high priority in new commissions. As an accompaniment to madrasas, mosques, and other public service establishments, tombs were ensured a constant flow of well-wishers, eternally securing the prestige of the owner.

Radha J. Dalal

Art History Program, VCUarts Qatar

In Focus

Sultan Hasan’s Madrasa Complex

Cairo, Egypt

In the tumultuous years of the fourteenth century, Bahri Mamluks (former slaves of Turkic origin) ruled over an extensive region across Egypt with their capital in Cairo.

More