Scribal and Pictorial Traditions

Museum of Islamic Art Spotlight Object

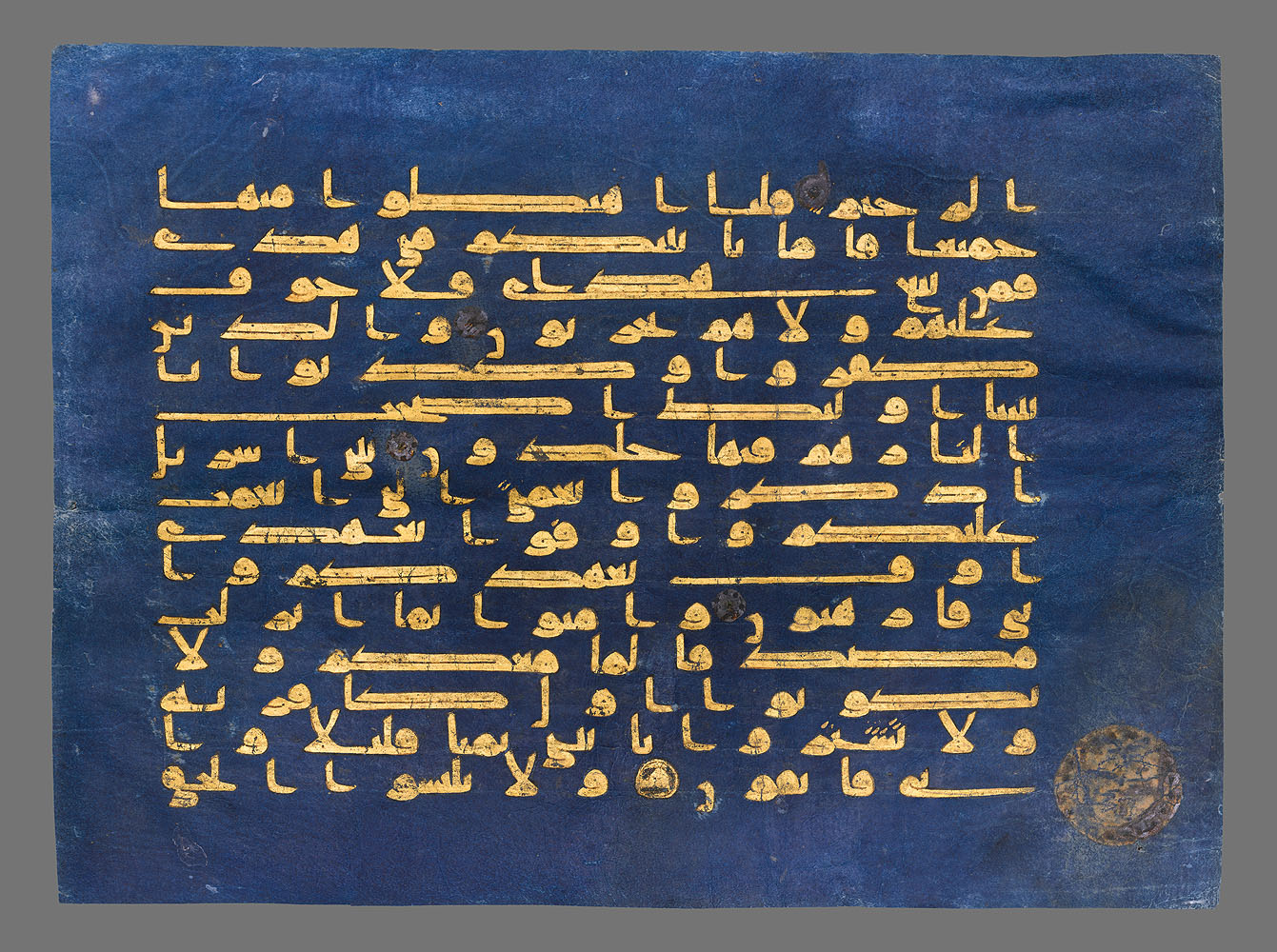

Folio of the "Blue Qur’an"

Fatimid, North Africa

10th century

Ink and gold on dyed parchment

28 × 38 cm

MS.8.2006

Credit: Museum of Islamic Art

This folio was part of a copy of the Qur’an known as the “Blue Qur’an.” Originally consisting of probably seven volumes, it may have been produced as a commission for a ruler of the Fatimid dynasty in Ifriqiya. Written in kufic script using gold and ink on dyed parchment, this manuscript likely shows the influence of the production of similar manuscripts in the Byzantine and Carolingian contexts. According to historical sources, the manuscript was recorded in the mosque library of Kairouan in the thirteenth century. Many pages were disseminated during the Ottoman period and are included in several collections now.

Mounia Chekhab-Abudaya

Curator for North Africa and Iberia, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar

The Big Picture

The written word in Islamic art holds great significance. This is due in part to the holy Qur’an and the message revealed within. But it is also partly due to the malleability of the Arabic script, which lends itself quite well to decorative experimentation. Pre-Islamic Arabia had a rich literary tradition circulating primarily through oral transmission. With the advent of Islam, however, the rising need for written documentation necessitated systemizing the Arabic script for ease of legibility and to eliminate the chance of misinterpretation. Under the aegis of Caliph Abd al-Malik, the Arabic script became more regularized, and its use spread from parchment to inscriptions on buildings, and from Umayyad administrative markers to minted currency. Indeed, early Islamic coins, deriving inspiration from Byzantine and Sassanian coinage, simultaneously presented a portrait of the caliph and the shahada, or profession of Islamic faith, in Arabic script.

The Qur’an was revealed entirely in verse and fully written down nearly twenty years after Prophet Muhammad’s passing. Scribes copied the holy text in vertical (relatively rare) and horizontal formats. In due time, ornamentation proliferated with delicate geometric and organic patterns, colored backgrounds and borders, application of gold leaf, and floriated cartouches separating suras (chapters) and medallions indicating ayat (verses). Similar to sacred architecture, the scripture of the Islamic faith never included figural representation.

Pictorial illustrations flourished in other types of texts, including epics, histories, and scientific treatises. Classical texts translated from Greek into Arabic, as well as texts of new advancements, were often illuminated much in the same way that primers for physics, medicine, and botany are today. These would have an immense impact on learning in the medieval Mediterranean and eventually lead to the Renaissance in Europe.

Manuscript production reached new heights after the introduction of paper from China and further changes to the Arabic script. While paper was cheaper than parchment, the expense involved in the creation of a single illustrated manuscript remained quite exorbitant. Books embodied the combined efforts of many hands, from papermakers to scribes, illustrators to binders. As such, illustrated books were largely produced in royal ateliers and mainly consumed by wealthy members of the ruling classes. Persian manuscripts, especially from the Timurid and Safavid periods, were held in high esteem, and their style influenced painting traditions in Mughal India and Ottoman Turkey.

Radha J. Dalal

Art History Program, VCUarts Qatar

In Focus

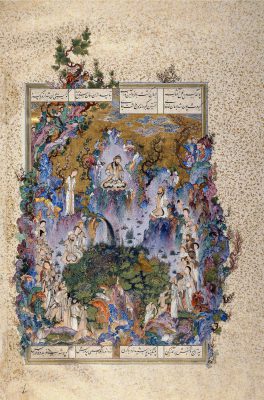

Tahmasp Shahnama

Aga Khan Museum, Toronto

While Persian painting had achieved immense sophistication and international recognition by the sixteenth century, it was during the rule of the Safavid Shah Tahmasp that remarkable innovations elevated the arts of the book further.

More

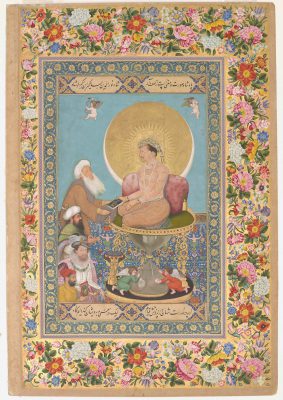

Jahangir Presenting a Book to a Sufi Shaikh

Freer and Sackler Galleries of the Smithsonian, Washington, DC

Mughal emperors admired Persian illustrated manuscripts and established royal ateliers to train local artists. During Akbar’s reign (r. 1556–1605), Jesuit missionaries bearing diplomatic gifts introduced European modes to the Mughal court.

More